We say that \(m\) divides \(n\), denoted by \(m \ | \ n\), provided that there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(n=km\). If so, which method would you prefer and why? Definition 3.20

After you solve a task using one method, ask yourself if you can solve the same task using another method(s).

#Basic number theory proofs free#

In this section, you are free to choose any method you want to solve the tasks. In other words, why it is not possible for an integer to be not odd and not even?) Subsection 3.4 Which one to choose? (Note that this does not show the complete statement of the Parity Theorem because we have not explained why every integer must be either odd or even. Let us show the second part of this theorem by proof by contradiction, namely, show that an arbitrary integer cannot be both odd and even. Task 3.19īy the Parity Theorem, we know that every integer is either odd or even but not both. The usual rst such theorem is Theorem O(q) D(q):That is, the number of partitions of n into odd parts equals the number of partitions of n into distinct parts. Use proof by contradiction to show that if \(m-n\) is odd, then \(m+n\) is odd. Basic De nitions Many classical theorems in partition theory state identities between such classes which would not be obvious from a casual inspection. If that is still not possible, try proof by contradiction at the end. If that is not possible, then try proof by contrapositive. In general when we prove a theorem of the form \(P \Rightarrow Q\), we do not recommend to start by trying to use proof by contradiction. Compare your proof with the proof by contrapositive in Task 3.15, which one do you like and why? Use proof by contradiction to show the theorem: For any integer \(n\), if \(n^2-6n+5\) is even, then \(n\) is odd. In fact, different people might find different contradictions. You would have to find your own contradiction. One unsettling feature of this method is that we may not know at the beginning of the proof what the statement \(R\) is going to be.

Hence \(R\) and \((\sim R)\) are true at the same time, which is a contradiction! Hence \(P\) is true. There in you can find explanations why Euclid's proof is valid in constructive mathematics as it is proof by negation.Suppose that \(P\) is true. Have to offer, if any? I shall attempt to answer these questions. How then can a mathematician find out what constructive mathematicsįeels like? What new and relevant ideas does constructive mathematics Principles and contains only trivial mathematics, while advancedĬonstructive texts are impenetrable, like all unfamiliar mathematics. Text about constructivism spends a great deal of time explaining the In favor of constructivism but are not at all convinced by them, and inĪny case they may care little about philosophy. On the odd day, a mathematician might wonder whatĬonstructive mathematics is all about.

#Basic number theory proofs series#

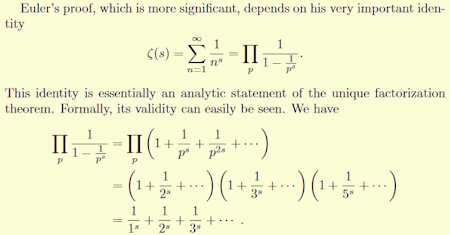

However, that is not true for sufficiently large $N$, and so we have our contradiction, and the series diverges.Īlthough this is an old post it is instructive to cite the following study on constructive mathematics which clears some common misconceptions related to constructive mathematics by people trained exclusively in classical mathematics.įor example the difference between proof by negation ( valid in constructive mathematics) vs proof by contradiction ( not valid in constructive mathematics in general)įIVE STAGES OF ACCEPTING CONSTRUCTIVE MATHEMATICS (ANDREJ BAUER)Ībstract. Ring Theory (Math 113), Summer 2014 James McIvor University of California, Berkeley AugAbstract These are some informal notes on rings and elds, used to teach Math 113 at UC Berkeley, Summer 2014. Since those two categories include all the positive integers $\leq N$, we must have $N/2+2^k \sqrt N \geq N$. An upper limit on the number divisible by a "big" prime is $N/2$ (this comes from the assumption that the sum of the reciprocals of the big primes is $\leq 1/2$), and an upper limit on the number not divisible by a "big" prime is $2^k\sqrt N$. We can divide the positive integers $\leq N$, for arbitrary N, into two groups: those that are divisible by a "big" prime, and those that are not. The key idea is not that Euclid's sequence $\ f_1 = 2,\ \ \color$ the "big" primes. See Hardy and Woodgold's Intelligencer article for a detailed analysis of the history (based in part on many sci.math discussions ). Euclid's proof was in fact presented in the obvious constructive fashion explained below. Due to a widely propagated historical error, it is commonly misbelieved that Euclid's proof was by contradiction.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)